Topics

All

Civil Services in India (26)

Ethics, Integrity and Aptitude

» Chapters from Book (11)

» Case Studies (8)

Solved Ethics Papers

» CSE - 2013 (18)

» CSE - 2014 (19)

» CSE - 2015 (17)

» CSE - 2016 (18)

» CSE - 2017 (19)

» CSE - 2018 (19)

» CSE - 2019 (19)

» CSE - 2020 (19)

» CSE - 2021 (19)

» CSE -2022 (17)

» CSE-2023 (17)

Essay and Answer Writing

» Quotes (34)

» Moral Stories (18)

» Anecdotes (11)

» Beautiful Poems (10)

» Chapters from Book (5)

» UPSC Essays (40)

» Model Essays (38)

» Research and Studies (4)

Economics (NCERT) Notes

» Class IX (14)

» Class X (16)

» Class XI (55)

» Class XII (53)

Economics Current (51)

International Affairs (20)

Polity and Governance (61)

Misc (77)

Select Topic »

Civil Services in India (26)

Ethics, Integrity and Aptitude (-)

» Chapters from Book (11)

» Case Studies (8)

Solved Ethics Papers (-)

» CSE - 2013 (18)

» CSE - 2014 (19)

» CSE - 2015 (17)

» CSE - 2016 (18)

» CSE - 2017 (19)

» CSE - 2018 (19)

» CSE - 2019 (19)

» CSE - 2020 (19)

» CSE - 2021 (19)

» CSE -2022 (17)

» CSE-2023 (17)

Essay and Answer Writing (-)

» Quotes (34)

» Moral Stories (18)

» Anecdotes (11)

» Beautiful Poems (10)

» Chapters from Book (5)

» UPSC Essays (40)

» Model Essays (38)

» Research and Studies (4)

Economics (NCERT) Notes (-)

» Class IX (14)

» Class X (16)

» Class XI (55)

» Class XII (53)

Economics Current (51)

International Affairs (20)

Polity and Governance (61)

Misc (77)

Women in Judiciary

Of 245 judges who have made it to India’s highest court, including the current judges, less than 3.3% have been women. No woman has served as the Chief Justice of India. In the 70 years since its inception, the Supreme Court has had only 8 women judges. In the lowest level of the judiciary however, there is greater gender representation. Judicial Reforms Initiative at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a think tank, wrote in January 2020 that in 17 states, between 2007 and 2017, 36.45% of judges and magistrates were women. In comparison, 11.75% women joined as district judges through direct recruitment over the same period, according to data from 13 states. Why don’t women judges in the lower judiciary progress to the higher levels? This essay takes a look at the reasons and the steps taken to rectify the issue.

Recent development

Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana in September 2021 backed 50% representation for women in judiciary.

Recently, 3 women - Justice Hima Kohli, Justice Bela M Trivedi and Justice BV Nagarathna - were sworn in on 1 September to the Supreme Court of India.

Historical context

Legally, the appointment of Supreme Court and High Court Judge should be done by the President of India with the consent of Chief Justice of India provided under Part V & VI I of Constitution.

The existing norm followed in India - As per the Three Judges Cases – (1982, 1993, 1998), a judge is appointed to the Supreme Court and the High Courts by the President of India from a list of names recommended by the collegium – a closed group of the Chief Justice of India and the senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, for appointments to the Supreme Court, and they, together with the Chief Justice of a High Court and its senior-most judges, for appointments to that court.

This has resulted in a Memorandum of Procedure being followed, for the appointments. Judges used to be appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Union Cabinet. After 1993, as held in the Second Judges’ Case, the executive was given the power to reject a name recommended by the judiciary. However, according to some, the executive has not been diligent in using this power.

The court held that who could become a judge was a matter of fact, and any person had a right to question it. But who should become a judge was a matter of opinion and could not be questioned. And as long as an effective consultation takes place within a collegium the opinion cannot be scrutinised.

Ongoing debate

The retirement of Justice Indu Malhotra from the SC in March 2021 stirred the debate around gender sensitisation and representation in the judiciary. Supreme Court Women Lawyers Association (SCWLA) had moved to the Supreme Court seeking an order issuing directions to appoint more women lawyers, who are competent and deserving, in the Higher Courts of India. The contentions raised by the SCWLA presented many hard-hitting facts:

·The dreadful ratio of women judges overall to only 8 women in the Supreme Court since independence.

·Citing Articles 14 and 15(3) of the Constitution that promote and safeguard equality on the basis of gender, the application reiterated the need to have adequate representation of meritorious women.

The matter was heard by the bench headed by Chief Justice S.A. Bode, and many favourable statements were given, but the bench ultimately refused to pass any order ensuring affirmative action for fulfilment of the demands. CJI also remarked that he was told many women lawyers refuse to accept judge’s posts citing domestic responsibilities. However, it cannot justify the massive gap in the ratio of male to female judges appointed in High Courts.

Significance

·It is not only fair but also crucial to have a solid representation of women in the judiciary. Justice Indu Malhotra, in her farewell speech in March 2021, also mentioned that society benefits when gender diversity is found on the bench.

·Victims of sexual violence also feel more comfortable and confident to file complaints and seek justice when they find an adequate number of women justices in Courts.

·This is not to say that having women judges on the bench would always guarantee a fair judgement. But the lack of empathy depicted in many previous judgements on cases of sexual harassment and molestation could significantly reduce.

·Women judges will bring their own experiences to their judicial actions, and tend towards a comprehensive and empathetic perspective.

·It is a step towards achieving gender neutrality and equality in one of the most important organs of the country.

·Better female representation in the higher courts will act as a model to be replicated in all other institutions like the executive, army, etc.

Challenges

·The appointment of 3 new judges is just a first step. The skewed representation of female judges across the country needs to be addressed immediately for any real change.

·No data is centrally maintained on the number of women in tribunals or lower courts.

·There are only 17 women senior counsel designates in the Supreme Court, as opposed to 403 men.

·More women tend to enter the lower judiciary at the entry-level because of the method of recruitment through an entrance examination. The higher judiciary has a collegium system, which has tended to be more opaque.

·Even with an increasing number of women in the bar, there appears to have been no meaningful change in the likelihood of a female appointment in high courts.

·Many states have a reservation policy for women in the lower judiciary, which is missing in the high courts and Supreme Court.

·Factors of age and family responsibilities also affect the elevation of women judges from the subordinate judicial services to the higher courts.

·Many employed women quit the workforce mid-career for child care responsibilities.

Way forward

Simply appointing a woman CJI wouldn’t solve the system and the decision-makers from further accountability. The recent 3 appointments should be treated as a beginning to the sea of changes that require to be brought into the judicial system and not as the ultimate goal:

·Systematic change - system presiding over appointments of Judges must be independent, accountable, and transparent.

·Ensure that more female students are enrolled in law colleges.

·Establish certain reservation policies to overcome the initial disparity in number of females in the system.

·Improve infrastructure and facilities to provide safe working conditions for women.

With more women in courts, gender discrimination and bias would likely reduce. Greater gender diversity could change the culture of the organisations.

Sources:

Hindustan Times

The Hindu

BBC India

Lawoctopus

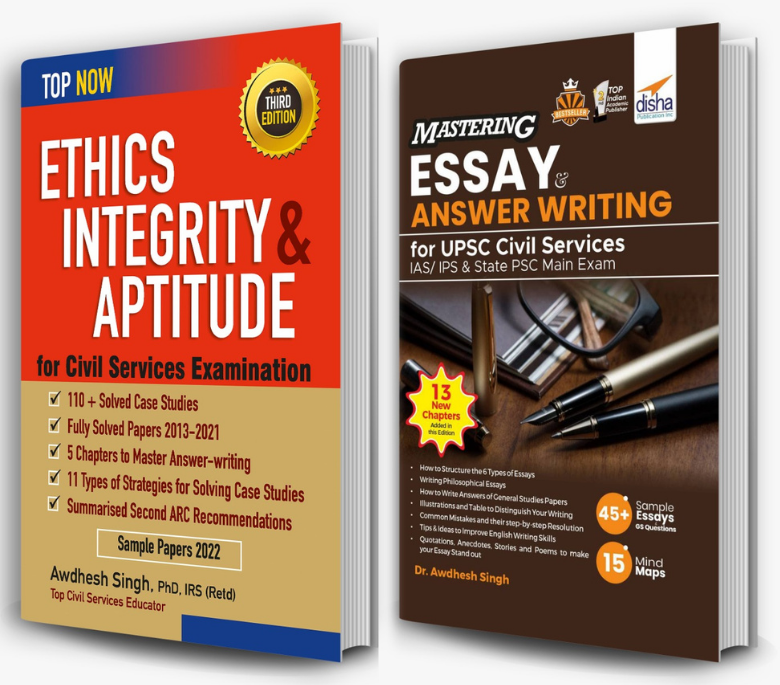

Looking for a One-stop Solution to prepare for ‘Ethics, Integrity, and Aptitude’ and ‘Essay and Answer Writing’ for UPSC?

Buy Dr. Awdhesh Singh’s books from the links below-

Buy Dr. Awdhesh Singh’s books from the links below-

Ethics, Integrity & Aptitude for Civil Services Examination

Amazon - https://amzn.to/3s1Qz7v

Flipkart - https://bit.ly/358N2uY

Mastering Essay & Answer Writing for UPSC Civil Services

Amazon - https://amzn.to/3JELE2h

Flipkart - https://bit.ly/3gVIwmv

| Related Articles |

| Recent Articles |